As African countries push towards achieving universal health coverage (UHC), reforming provider payment mechanisms in Primary Health Care (PHC) has emerged as a pivotal strategy to improve efficiency, quality, and equity in healthcare delivery. These mechanisms serve as powerful levers to advance health policy goals and strengthen PHC systems, as they determine how funds are transferred from healthcare purchasers to providers, thereby influencing provider behaviour, service delivery, and ultimately, health outcomes.

PHC providers are often the first point of contact between communities and the healthcare system, making their role in delivering comprehensive and equitable care crucial. Globally, evidence shows that strong PHC sectors are associated with improved access to essential health services, greater equity, higher patient satisfaction, and more cost-effective health outcomes. Strategic payment mechanisms can incentivise PHC providers to offer more integrated, continuous, and coordinated care, aligning closely with PHC principles, which is fundamental to achieving these positive outcomes.

Different African countries have adopted various provider payment mechanisms to improve health outcomes, offering unique insights into what works and the challenges that persist. In Ghana, for instance, capitation was introduced in 2012 under the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) to improve the delivery of PHC services. Providers receive a fixed payment per registered patient, encouraging a shift towards preventive care and more efficient use of resources. Despite initial resistance from both providers and patients, the system has shown promise by improving cost control and the predictability of healthcare expenditure. However, ensuring accurate population data and appropriate risk adjustment mechanisms is critical to achieving equitable capitation calculations.

In Rwanda, the implementation of a nationwide performance-based financing (PBF) programme in 2005 has been transformative. By linking provider payments to predefined performance indicators, the system incentivised improvements in maternal and child health, HIV/AIDS services, and the overall quality of care. Notably, there was a 23% increase in institutional deliveries and a 20% reduction in health worker absenteeism. However, Rwanda’s experience also highlighted the importance of strong verification systems to ensure that the improvements reported were genuine and not manipulated for financial gain.

Nigeria has taken a different approach with its pilot of Decentralised Facility Financing (DFF) in several states, allowing PHC facilities to manage funds independently, based on their specific needs. Key features of the DFF model include the formation of facility health committees with community involvement, the development of operational plans tailored to each facility, and the direct transfer of funds to facility bank accounts, financial management and reporting training for staff, and regular supervisory visits and audits to ensure accountability. These initiatives have empowered PHC facilities with greater autonomy and improved community engagement in healthcare decision-making. However, the pilot also underscored the need for significant capacity building in financial management at the facility level and the importance of establishing strong accountability mechanisms.

Kenya’s National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF) employs a mixed payment system, combining capitation for outpatient services with case-based payments for inpatient care. This hybrid approach aims to balance the incentives provided by different payment mechanisms, improving access to both outpatient and inpatient services and creating a better balance between preventive and curative care. While this approach has enhanced cost predictability for the NHIF, it has also presented challenges, such as administrative complexity and the need for regular review and adjustment of payment rates, as well as the importance of strong regulatory frameworks to maintain quality of care.

In Burkina Faso, the government has prioritised health system reforms and investments in expanding coverage of quality services for vulnerable communities. Five major schemes underpin this effort: Gratuité (a national free healthcare programme for women and children under five), crédits délégués (delegated credits), crédits transférés (transfers to municipalities), community-based health insurance, and occupation-based health insurance. While these schemes have increased service utilisation, they also face sustainability challenges, delayed payments, and the need for substantial investments in health worker capacity and health information systems.

The experiences from these countries provide valuable lessons for the design and implementation of provider payment reforms in Africa. First, payment mechanisms should be tailored to the specific health system context, considering factors such as health financing structures, provider capacity, and overarching health system goals. Secondly, involving key stakeholders—including healthcare providers, policymakers, and communities—early on is crucial to ensuring the successful implementation and sustainability of reforms. Gradual rollout of reforms allows for learning and adjustment, minimising disruptions to healthcare delivery. It is also vital to conduct robust monitoring and evaluation to assess the impact of these reforms on healthcare quality, access, and costs, ensuring continuous improvement.

Capacity building is another key element, as strengthening the financial management, data collection, and quality improvement skills of healthcare providers and administrators is critical to the success of payment reforms. Finally, provider payment reforms should be integrated with broader health system strengthening efforts, such as improving health information systems and quality assurance frameworks, to ensure holistic improvements.

In conclusion, reforming provider payment mechanisms within African PHC systems holds significant potential to improve efficiency, quality, and equity in healthcare delivery. However, these reforms are complex and require careful planning, phased implementation, and continuous evaluation. By learning from diverse experiences across the continent, policymakers can design payment systems that significantly contribute to achieving universal health coverage in Africa. As countries continue to experiment with and refine their payment mechanisms, sharing experiences and best practices will be essential. The journey towards optimising provider payment systems is ongoing, but the lessons learned thus far provide a strong foundation for future reforms.

About the Authors:

Charlotte Muheki, Technical Director, Primary Health Care, Health Systems Strengthening Directorate, Amref Health Africa.

Isha Sharma, Programme Officer, Country Engagement and Technical Initiatives, Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage, Amref Health Africa.

Ebubechi Nwaononiwu, Technical Officer, Evidence Generation and Learning (EGAL), Strategic Purchasing Africa Resource Centre (SPARC), Amref Health Africa.

Achuman Emoni stretches her hands, illustrating the vast distance she has travelled to reach the…

During a session held at Africa Health Agenda International Conference in Kigali, Rwanda, on 4th…

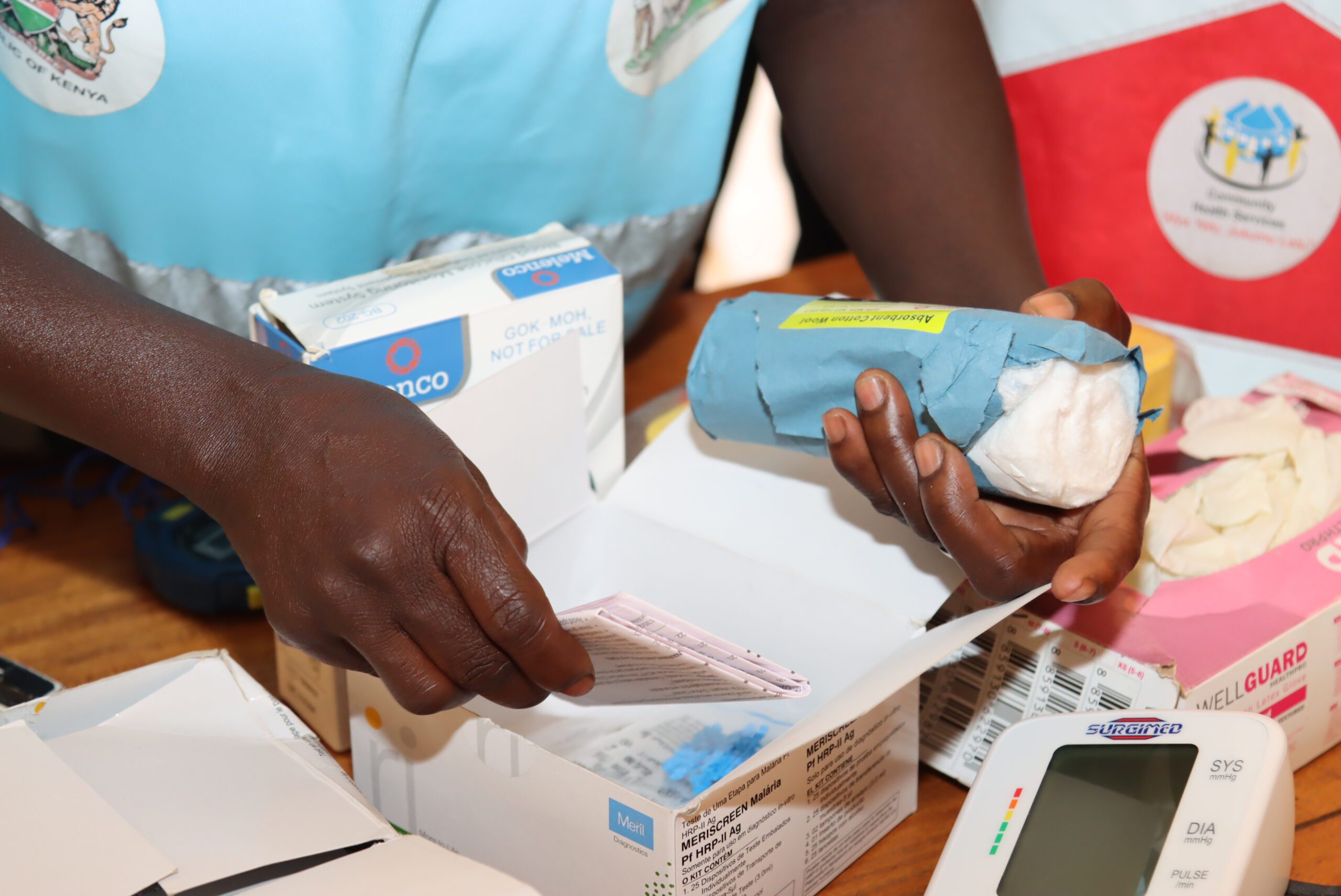

Amref Health Africa, in collaboration with the Turkana County Department of Health Services, introduced the…

Amref Health Africa, in collaboration with the Turkana County Department of Health Services, introduced the…

Over the past six years, Amref Health Africa has positioned itself as a leading voice…

Africa has made significant strides in advocating for health research and development, yet gaps in…