In 1986, Mzee Lepoo watched his father save their village from devastating floods. By observing bird movements and changes in the natural environment, his father accurately predicted the rains, helping the community prepare and mitigate disaster. Now at 68, Mzee Lepoo continues this legacy in Isiolo County’s Olerai community, using traditional knowledge to guide adaptation strategies in an era of worsening climate variability.

Lepoo still predicts weather patterns using generations-old methods like examining goats’ intestines, listening to how the wind moves, observing the moon’s position and noting insect, bird, and livestock behaviour. Winds blowing from the north signal an impending drought, prompting farmers to adjust planting schedules or switch to resilient crops. A crescent moon facing upward warns of a dry month, advising the community to delay ploughing.

Signs from nature, such as frogs croaking in streams or playful cattle, indicate approaching rains, triggering preparations for planting and rainwater harvesting. However, many manyattas lack proper gutters to collect significant amounts of water, underscoring the need for innovation to support the livelihoods of the pastoral communities.

Climate Challenges and the Role of Indigenous Knowledge

Similar to regions in the Arid and Semi-arid lands, Isiolo County faces severe climate challenges. Annual rainfall is often below 250 millimetres, and extended dry spells are becoming more frequent. Pastoralism, dryland agriculture, and small-scale vending are the region’s economic mainstays. However, environmental degradation, driven by deforestation, soil erosion, overgrazing, and artisanal mining, has made livelihoods increasingly precarious. Water sources are silting, grasslands are diminishing, and livestock must travel longer distances for forage. Smallholder farmers suffer declining yields, increasing food insecurity levels above the national average.

Despite these hardships, traditional knowledge has proved invaluable for climate adaptation. Indigenous forecasting methods help communities anticipate extreme events, such as droughts and storms, allowing them to adjust agricultural activities, ration resources, and protect their families. This knowledge, passed down through generations by word of mouth, remains central to community resilience.

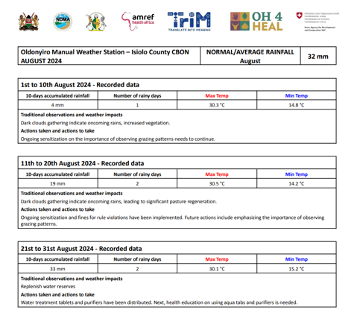

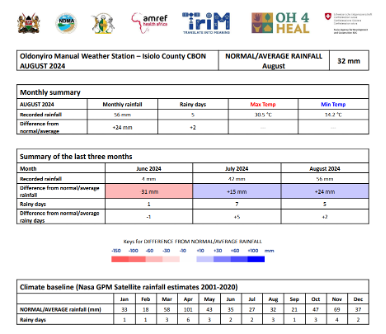

In Oldonyiro, health workers, local elders, teachers, veterinary department representatives and members of the Multi-Sector Innovation Platform (MSIPs) are pioneering new ways to integrate Indigenous knowledge into community planning. They share updates from a manual weather station with Isiolo County’s meteorological department. This station, consisting of a rain gauge and thermometer, is managed by trained health workers who collect data daily. At the end of the month, the data is compiled into a newsletter and circulated via smartphone messaging groups and local radio stations.

According to Dr Daniel Shikuku, a public health officer at the Oldonyiro sub-county health centre, these ground-level readings often align more closely with traditional forecasts than scientific data from satellites or radio transmissions. Because conventional methods are deeply rooted in local ecological contexts, they frequently provide smallholder farmers with more precise and actionable intelligence. “Through scenario planning, during the MSIP meetings, we blend Indigenous and scientific forecasting to develop community-driven climate adaptation strategies. By incorporating traditional knowledge and meteorological data, communities are better prepared for extreme weather events and can make informed decisions that protect their livelihoods. I trained in public health, but through the MSIPs, I learned that one health approach is the lynchpin to Universal health coverage. We cannot achieve a balance in the ecosystem without integration and collaboration,” he explains.

“This synergy of knowledge systems offers a template for effective climate action. Indigenous knowledge also informs health and nutrition policies: health workers advocate for growing indigenous crops like sorghum and finger millet rather than relying solely on hybrid maize varieties. These drought-tolerant cereals provide better nutrition for mothers and children and reduce vulnerability to erratic rainfall, especially for a county like Isiolo, a hotspot for acute malnutrition during dry seasons,” Dr Shikuku explains.

Sample of Oldonyiro manual weather station Monthly Newsletter

Preserving and Passing Down Indigenous Knowledge

The continued viability of Indigenous knowledge is under threat. Environmental degradation, deforestation, and shifting species distributions disrupt the natural indicators communities rely on. As tree species disappear and wildlife patterns change, traditional forecasting methods risk becoming less reliable.

“The survival of Indigenous knowledge depends on its transmission to younger generations,” says Mzee Lepoo. “If birds and insects no longer behave as they used to, our ability to predict weather will diminish. We must involve young people through education, mentorship, and community programs to keep these techniques relevant in today’s world.”

In Isiolo County, the wisdom of elders like Mzee Lepoo underscores the vital role of Indigenous knowledge in building resilient communities.

Project Brief:

The Multi-sector innovation platform is an initiative implemented by Amref’s One Health for Human, Environment, Animal, and Livelihoods (OH4HEAL or HEAL) project. It addresses the challenges arid and semi-arid areas in the Greater Horn of Africa face, including recurrent droughts, infectious disease outbreaks, and limited access to essential services. By leveraging human, livestock, and rangeland health interconnectedness, the project applies a One Health approach to improve resilience and livelihoods in pastoral communities across Ethiopia, Somalia, and Kenya. Through participatory and integrated One Health Units (OHUs), HEAL coordinates service delivery among government, private providers, and communities to sustainably enhance health services, bolster resource management, and mitigate climate change impacts. The project, implemented by VSF-S, Amref, and ILRI, focuses on context-specific strategies to empower communities to adapt to dynamic environments.

Author: Edna Mosiara, Communications Officer, Amref Health Africa in Kenya