The era when Africa could rely on foreign aid for its health priorities is coming to an end—signaling not a crisis, but a defining opportunity. Development assistance is shifting from broad solidarity to more conditional, politically aligned engagement. Recent shifts—exemplified by the current U.S. foreign aid reforms and broader donor cutbacks—confront African nations with a hard choice: build greater self-reliance or remain vulnerable to the unpredictability of external funding. Yet in this urgency lies Africa’s moment of hope and agency: to reimagine and reclaim its health future through leadership, innovation, and strategic investment.

Several African countries are already advancing health sovereignty through smart financing and governance reforms—driven by presidents, health and finance ministers, governors, and development partners. Rwanda’s community-based health insurance now covers over 85% of the population, supported by national subsidies and community health worker cooperatives. Ethiopia has expanded its community-based insurance through its government-led Health Extension Programme. Ghana’s model—partly funded through a national health insurance levy—has significantly reduced out-of-pocket spending. These examples prove that Africa can sustainably finance and govern its health systems beyond aid.

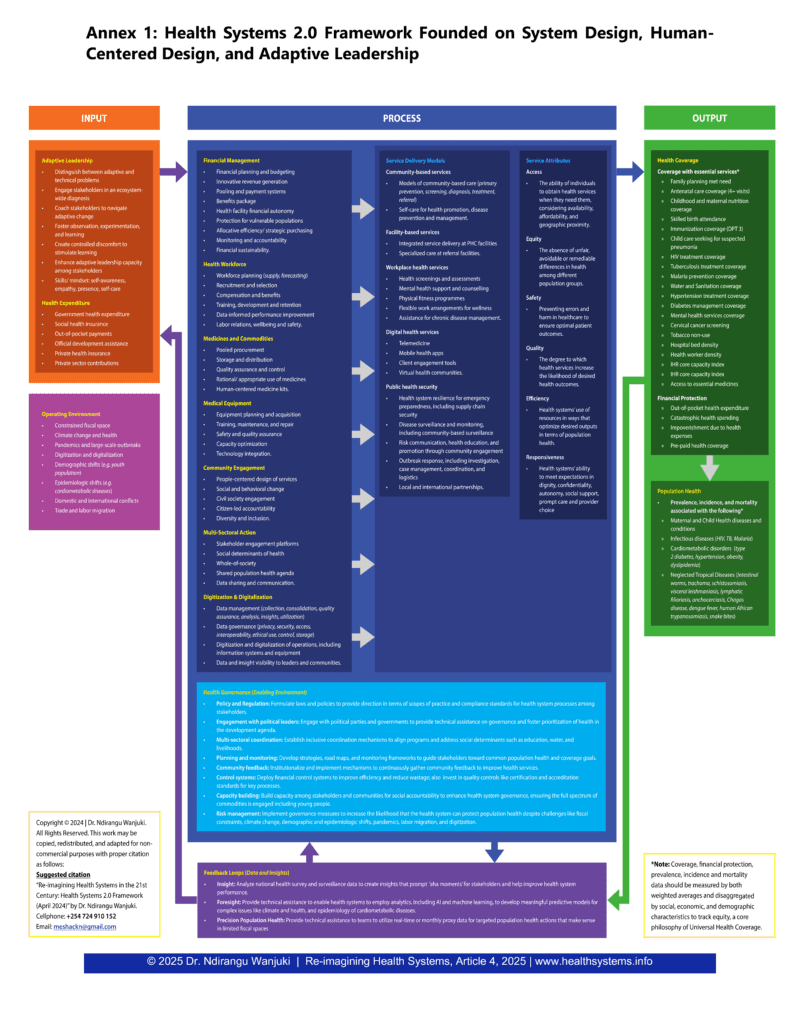

Africa must now reimagine its health systems through a new, context-specific framework. Health Systems 2.0—anchored in systems thinking, adaptive leadership, and human-centred design—offers a pathway to build resilient, self-financed, people-centred systems.

The Financing Gap

Africa currently invests $116 per person in health.—far below the US$249 benchmark needed for basic service coverage, and just a fraction of what high-income countries invest. Historically, donor funding helped bridge part of this gap, but that cushion is shrinking. Donor fatigue, shifting geopolitical priorities, and evolving criteria—reflected in reforms during the Trump administration—have made reliance on external support increasingly precarious.

Overdependence on donors can delay necessary domestic reforms and expose governments to external shocks. To secure long-term resilience, African nations must embrace a new financing posture—one that blends catalytic donor support with robust domestic resource mobilisation—anchored in adaptive leadership, stronger governance, and prevention-focused investment. Done well, this shift will strengthen the foundation for smarter fiscal policy, local innovation, and lasting national ownership of health priorities.

An Evolving Burden—And A Clash with Old Models

Africa’s disease landscape is evolving. While infectious diseases remain a threat, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like hypertension, diabetes, and cancers are rising sharply. Most health systems, originally designed for acute care, are ill-prepared for these chronic burdens. As Dr. Githinji Gitahi warns: “Africa has a big risk of collapse of health systems in the next few years because of NCDs […] 50% of all admissions in a typical African hospital are NCDs, yet 80% of NCD care is paid out of pocket, and governments don’t have money to actually take care of NCDs.”

The sustainable solution lies in prevention, early screening, and resilient primary healthcare—core to the Health Systems 2.0 model, moving away from the “inefficient equilibrium” where systems appear stable superficially yet fail to deliver meaningful health outcomes due to underlying flaws in design or leadership.

Three Essential Shifts Africa Must Make

Adaptive Leadership Over Technical Expertise

Africa’s toughest health challenges are not just technical—rising rates of non-communicable diseases, high maternal mortality, and chronically underfunded frontline preventive and treatment services—they are adaptive. They demand leadership that mobilises stakeholders, drives institutional transformation, and fosters a culture of learning.

Adaptive leadership (Heifetz et al., 2009) distinguishes between technical problems and adaptive challenges, which require deeper structural shifts, often without clear precedents. Addressing the latter demands leadership that fosters learning, experimentation, and iteration—distributing problem-solving across systems and cultivating shared ownership of change. Rwanda’s experience with community-based health insurance exemplifies this. Under sustained national commitment, Rwanda achieved over 80% health insurance coverage, dramatically reduced child and maternal mortality, and lowered catastrophic health spending. Rwanda expanded this model while integrating HIV investments into primary care and scaling access to other essential services. Between 2000 and 2012, under-five mortality declined by more than 60%, maternal mortality dropped from 910 to 340 per 100,000 live births, and childhood immunisation coverage reached 97%.

A nationally representative survey further revealed the insurance scheme reduced annual per capita out-of-pocket spending by approximately US$12—an 83% drop from baseline—and significantly lowered catastrophic health expenditures, accelerating progress toward universal coverage.

These gains were not achieved through technical fixes alone, but through adaptive leadership that aligned policy with community realities, embedded iterative learning, and cultivated shared ownership of health. Citizens increasingly came to view health insurance not as charity, but as a shared national and household investment.

Prioritise Community-Led Prevention at the Centre of Health Systems

Prevention is the smartest and most cost-effective strategy for building healthier populations and fiscally resilient systems. Community-based approaches—especially those rooted in trusted, locally embedded health workers—are central to making prevention real and scalable.

Ethiopia’s Health Extension Programme (HEP), launched in 2003, shows how government-led, community-based models can drive measurable population health gains and accelerate progress toward universal health coverage. As part of broader reforms, HEP deployed more than 42,000 trained health workers to rural communities, expanding access to essential services. It contributed to increased uptake of maternal and child health interventions, improved sanitation, and stronger disease prevention practices—supporting a 67% reduction in under-five mortality and a 71% decline in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015.

Nigeria’s Ondo State offers another compelling example. The Abiye Safe Motherhood Programme—fully funded by the state and free of cost to clients—was associated with a 70% drop in maternal mortality, from 708 to 208 deaths per 100,000 live births between 2010 and 2014. This success stemmed from the removal of financial barriers, expanded access to skilled care, and a community-based tracking system that followed pregnant women from conception to delivery.

Kenya provides further evidence: during the COVID-19 pandemic, community health workers reached over 2.5 million household members across 27 counties within weeks, helping sustain essential health services. These examples show that deliberate, systems-level investment in trusted, prevention-first strategies can deliver meaningful population health gains—and move countries beyond the inefficiencies of reactive, hospital-centric models.

In Health Systems 2.0, prevention must be central, not peripheral. Governments should allocate at least 10% of health budgets to scalable, prevention-first approaches that shift care upstream, ease hospital burdens, and deliver measurable health and economic gains. Countries that invest in prevention save more lives and build stronger, more fiscally resilient health systems.

Strengthen Governance to Unlock Domestic Financing

Africa’s path from aid dependence to resilient health systems hinges on a renewed social contract—anchored in public trust, equity and inclusivity, transparency, and accountability. Promising pathways are already emerging: Ghana’s VAT-backed National Health Insurance Levy, Rwanda’s community health worker cooperatives, and Ethiopia’s locally managed community-based insurance schemes reflect early models of locally anchored health financing.

Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS)—funded through dedicated domestic taxes and citizen contributions—remains a promising model, despite equity challenges. Recent analysis shows that NHIS coverage expanded to approximately 54% of the population by 2021, improving access to essential services. Yet catastrophic health expenditure continues to rise, particularly for hospital care and medical supplies, with rural, northern, and low-income households most affected. These patterns highlight the need to strengthen governance through an equity lens—ensuring that reforms protect the most vulnerable as they expand coverage.

Trust in health systems is earned—not assumed. In Kenya, Amref Health Africa has used community scorecards—through the Community Systems Strengthening approach, supported by the Global Fund—to ensure that community voices shape national health decisions. These tools have strengthened accountability and responsiveness in HIV, TB, and malaria programmes by aligning services with lived community experience. This is Precision Population Health in practice: listening not just to data, but to people—in context.

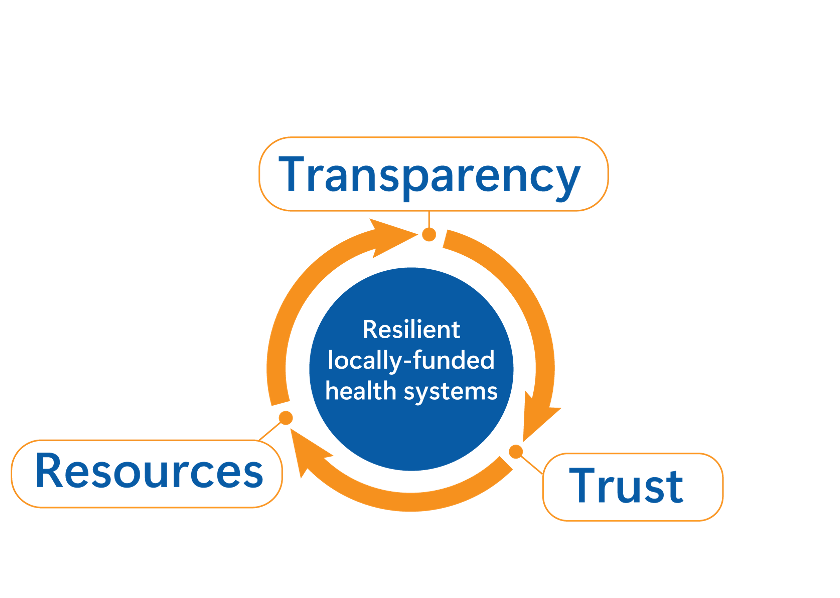

Strong governance sets off a reinforcing cycle: transparency builds trust, trust unlocks resources, and those resources sustain resilient, locally funded health systems (Figure 1).

Deploy Innovative Health Financing

Given Africa’s constrained fiscal space—with average health spending at US$116.9 per capita in 2020, significantly below the global average of US$1,205.6—traditional domestic financing approaches alone will not close the gap.

Innovative financing mechanisms provide pragmatic solutions for sustainably increasing domestic investments in health. Kenya’s Facility Improvement Fund (FIF) is a compelling example. As highlighted in the WHO Health Financing Progress Matrix assessment, Kenya’s FIF Act (2023) empowers public health facilities to retain, manage, and transparently account for their own revenue. When fully operational, this model could significantly improve resource management, service quality, and overall health outcomes—particularly at the primary care level.

Additionally, health taxes—such as those successfully implemented in South Africa and Brazil—represent another proven strategy. These excise taxes on tobacco, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages simultaneously raise critical revenue for health services and reduce the consumption of products that drive non-communicable diseases (NCDs). The World Bank underscores that well-structured health taxes can significantly lower the burden of NCDs while generating sustainable financing for health priorities.

However, raising additional funds alone is insufficient. Resources must be strategically allocated, transparently managed, and rigorously governed. Investments should prioritise preventive and primary healthcare services, ensuring every dollar delivers maximum health impact. Africa’s path to sustainable health financing depends not merely on innovative funding approaches, but also on accountable governance systems that earn public trust and tangibly improve population health.

Conclusion & Call to Action

“Beyond aid” is Africa’s call to reclaim agency over its health future. Declarations alone will not suffice; governments must visibly prioritise health, actively invest in prevention, and nurture adaptive leadership at every level. Finance ministers must recognise health expenditure as strategic investment, and health ministers must decisively shift their focus from managing illness to promoting wellbeing.

Today’s choices will shape health outcomes for generations. By embedding adaptive leadership, expanding community-led prevention, and strengthening governance to unlock domestic financing, and adopting innovative financing mechanisms, the continent can build resilient, self-financed, and people-centred health systems. This approach—rooted in systems thinking, adaptive leadership, and human-centred design—forms the foundation of Health Systems 2.0, illustrated in Annex 1, and offers a pathway to lasting impact and dignity for Africa’s people.

Dr. Meshack Ndirangu Wanjuki is a health systems strategist and Country Director of Amref Health Africa in Kenya. He champions adaptive leadership, health sovereignty, and resilient, people-centred health systems for Africa.