One day in May last year, Violet Chemesunte, a community health volunteer in Kibera, the largest slum in Nairobi, got a call from a colleague worried about a woman she had visited who kept coughing.

She asked if Chemesunte could go round and convince the 37-year-old woman, a single mother to three young children, to seek medical help. She suspected tuberculosis (TB), and feared it might already be too late.

“I went there and she was very sick,” remembers Chemesunte. “She didn’t want to go to hospital because she was scared she might have Covid and would be taken into quarantine. The government had enforced very strict measures at that time and there was a lot of fear around.”

Chemesunte spoke to the woman about TB, which has some similar symptoms to Covid, and persuaded her to get tested at a nearby site. It came back positive.

Two weeks later, before she could start treatment, she was dead. Her children, aged between nine and 13, tested negative and have since left Nairobi to live with their elderly grandmother.

“It was very sad,” says Chemesunte. “She didn’t need to die. TB is curable. The only thing you need is to be diagnosed early enough.”

TB is one the world’s deadliest infectious diseases. It kills more people than HIV and malaria combined. Last year in Kenya 21,000 people died of TB, four times the number of those who have died from Covid-19 since the pandemic began.

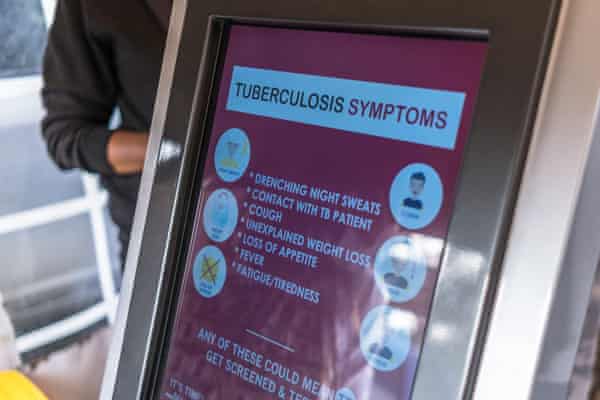

The disease is airborne and can lie dormant in someone infected with the bacteria. When a person develops active TB, symptoms may include a cough, fever, night sweats and weight loss. Left untreated, TB kills about half of those affected. Someone with active TB can infect five to 15 others through close contact over the course of a year.

The World Health Organization revealed in October that Covid-19 had reversed years of global progress in tackling TB, and for the first time in over a decade, deaths had increased.

Kenya is one of the 30 countries with the majority (at least 83%) of cases. Last year, around 140,000 people in Kenya were estimated to have TB, according to the country’s Ministry of Health.

Covid also meant that the number of “missing people” with TB – those who go undetected, untreated and unreported – increased. Nearly half of people with TB in Kenya last year were likely to have missed out on diagnosis and treatment. An estimated 15% reduction in case finding was “largely attributable to the pandemic”, according to the Ministry of Health’s national tuberculosis, leprosy and lung disease programme annual report.

Restrictions on movement, patients avoiding health facilities, the repurposing of health services and workers to cater for the pandemic, and stigma related to similar presentations of Covid-19 and TB all contributed.

Against this backdrop is a lack of funding to tackle the disease. Masini says less than half of Kenya’s plan to tackle TB has adequate funding. One concern is lack of diagnosis in children; two-thirds of cases in those under 15 are missed, he says.

Masini is aghast at what he sees as an imbalance of attention and political will between Covid and TB. While Kenya’s president is fully in charge of the Covid response, with regular ministerial briefings and readily available data, this is not the case with TB, he says.

The number of deaths from TB is “the equivalent of two bus crashes in Kenya every day,” he adds. “[If that happened, it] would cause uproar. There would be high-level intervention. For TB, that urgency is not there – it’s not taken as an imminent danger. Resources are not aligned to the magnitude of the disease.”

Back in Kibera, where poor and cramped housing allows the disease to thrive, Anne Munene, project officer for Amref Health Africa, sits at a table outside a TB clinic. “Covid was an eye-opener,” she says. “What have we done wrong that we never got this attention for TB?”

She and her team at Amref Health Africa, which has received funding from the Global Fund, ran a campaign aimed at raising TB awareness at a community level, where so many cases are missed. Information on the dangers of TB were distributed to matatus, the minibuses used for public transport, and schools. The school curriculum is being updated to include TB, Munene says. The disease was also discussed on TV and radio chatshows.

Munene and her colleagues ran a competition asking businesses to suggest ways to find people with TB in the community. One innovation that has been adopted is an automated TB screening machine, or “ATM”. A community health volunteer helps people go through five automated questions, asking if they have experienced any TB symptoms. If they answer yes to any, they are encouraged to submit a sputum sample for testing.

The ATMs have been placed in frequently visited sites across Nairobi, including the train station and a compound in Kibera with various government and health services. From November 2019 to May 2021, about 80,000 people were screened for TB, Munene says. Of those, 262 tested positive and were put on treatment.

“These are things that have never been done,” she says. “To get 262 cases in the first 12 months that we would not have found otherwise shows we are filling a gap.”

The pandemic still threatens to curtail efforts and derail progress, but Munene also sees it as an opportunity. “Now we need to ride the wave of Covid to raise awareness of TB. We are still grappling with this.”

Article first published on http://www.allusanewshub.com/2021/12/03/she-didnt-deserve-to-die-kenya-fights-tuberculosis-in-covids-shadow/