Zanele Muholi is skeptical of me. The visual activist can’t quite make out who I am, where I come from, or what my background is over our teleconference call. We’ve been trying for days to find the perfect time that works with both of our busy schedules, as I’m on Eastern Standard Time and they’re currently in their home country of South Africa — vacillating between Johannesburg, Capetown, and Durban. For Muholi, it matters that I’m a Black transgender woman, even if I’m from the United States. And while they are reassured by our shared diasporic experience, the identity labels I use — that we use — that they used once upon a time to describe their sexual orientation and gender don’t suffice for them. The Durbanite is quick to explain that more specific terms discussing gender nonconformity and queerness don’t exist in their original Zulu language. “I identify as a human being at this stage because of gender fluidity, and to avoid being confused by what the society expects out of us,” they say. “I came out as a same-gender loving person, but because there was no Zulu name for it, I was called a lesbian. But we move on, transpire, transgress, and transform in many ways; so I’m just human.”

Zanele Muholi was born during an era of revolution. They entered the world in 1972, at the height of South African apartheid, on the east coast of KwaZulu-Natal, the province that was once the seat of the famed Zulu Empire. Around the time of their birth, anti-apartheid figures (like Steve Biko of the Black Consciousness Movement and Richard Turner of an emergent trade union movement) were influencing the social landscape of their country, while the Black Panthers were having a similar effect in the United States, some 9,000 miles away. The seeds for a post-apartheid South Africa were being planted, but Muholi and others wouldn’t see the discriminatory system legally uprooted until nearly two decades later.

“Whatever we have now is what we have worked for,” Muholi says matter-of-factly. “And we picked up the pieces for survival.”

Coming from an uneducated family with little means, the world-renowned artist never imagined their current status and occupation. Their father, Ashwell Tanji Banda, was a tradesman with a number of ancillary jobs who died just a few months after Muholi’s birth. Their mother, Bester, was a domestic worker who cleaned homes for white families — and like many Black mothers in our history, had to leave her own children to get the job done. But it wasn’t just Blackness that shaped how Muholi navigated their environment.

“Zanele was like a tomboy” in their youth, according to an interview with their older sister, Ntombizane, in Muholi’s 2010 documentary Difficult Love. As Muholi matured and found more language, they came out to their mother as a lesbian. “Once mom accepted, there was nothing we could do. The brothers couldn’t kick [them] out of the house,” Ntombianze explains in the film. Even with tremendous familial support, employment options remained limited, and most of their seven older siblings began working in local factories. Art just wasn’t in the cards yet.

“For one to survive, you’re told that you need to follow or do something serious, which might be nursing, teaching, or some clerical job,” Muholi says. “So, if you venture into art, it’s like a waste of time because art has never been recognized fully. Even the artists that came before earned less and had to work so hard. They made a lot of big mistakes by selling their arts for nothing.”

When Muholi reached adulthood in the early 1990s, a new future was on the horizon. Apartheid legislation was repealed, leading to the nation’s first multiracial democratic elections in 1994. A 21-year-old Muholi was one of the voters in the election that resulted in Nelson Mandela’s ascendance to the presidency. With the introduction of a new constitution in 1996 — which globally pioneered federal protections on the basis of sexual orientation — opportunities were expanding socially and culturally, and Muholi began a corporate career in Johannesburg. But the entrenched social limitations placed on them for their gender and sexual orientation remained. They were still seeing posters on street poles that demonized LGBTQ+ community members, and newspaper articles making light of the brutal violence and murders happening all over.

“That visual narrative wasn’t there in the way that I wanted to see it. And if it was, it was distorted,” Muholi says. “It was activism that led me to do the work that I do, because LGBTI media representation was so sensationalized and traumatic.” It was time for an intervention, one comprised of creation and a call to action.

In 2003, Muholi began a photography program at the Market Photo Workshop, an internationally prestigious school, gallery, and project space founded by renowned photographer David Goldblatt. In study, they honed in on the techniques that would help them capture the humanity of their own community. Their commitment to documenting the stories of rape and hate crime survivors and interest in intimate black and white photography led them to their first solo exhibition, “Visual Sexuality: Only Half the Picture,” at Johannesburg Art Gallery in 2004.

“Before I photographed people kissing, my focus was on the body,” Muholi says. “My beginning was more about questioning why our existence [as Black and LGBTQ+ people] interfered with so many people.”

Despite the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2006, the Black LGBTQ+ community was still facing extreme levels of violence for just being themselves. In particular, Black lesbians were, and continue to be, consistently targeted by cisgender heterosexual men for corrective or “curative” rape. This specific type of hate crime exists to “turn” its victims straight by forcefully engaging them with sexual acts and, sometimes, lethal violence. In the backdrop of Muholi’s work in the late aughts, a number of murders occurred, including that of Noxolo Nogwaza, a prominent LGBTQ+ rights activist who was stoned and stabbed to death.

In the aftermath of their first exhibition, Muholi (affected by the devastating circumstances still plaguing their community) began their most well-known work, the ongoing Faces and Phases series, which situates Black lesbians in a more documentarian, confrontational manner. The project’s essence comes from the figures not only being seen, but returning their gazes with a sense of existential defiance. The configurations of portraits are simple, while still deftly political.

“I’m producing this work as a concerned citizen of this country,” Muholi says. “I want to change what is written about us, what we are fed and forced to consume because we are told that we need to become better persons.”

This unabashed calling to depict the truth of their community placed Muholi head-to-head with controversy in 2010, when former South African Minister of Arts and Culture Lulu Xingwana reportedly stormed out of an exhibition featuring their signature works of women kissing in the nude.

“Our mandate is to promote social cohesion and nation-building. I left the exhibition because it expressed the very opposite of this,” Xingwana said in an interview at the time with The Guardian. “It was immoral.”

In turn, Muholi continued their work, undeterred. Soon after, they created Innovative Women and Trans(figures), which continued their exploration of the lives of lesbians, but delved deeper into the experiences of trans and gender nonconforming people in South Africa. During this period, they were also drawn to self-portraiture, excavating their own capacity to shape-shift at the whim of their artistic vision. It wasn’t until 2014 that they realized they had another, powerful project on their hands.

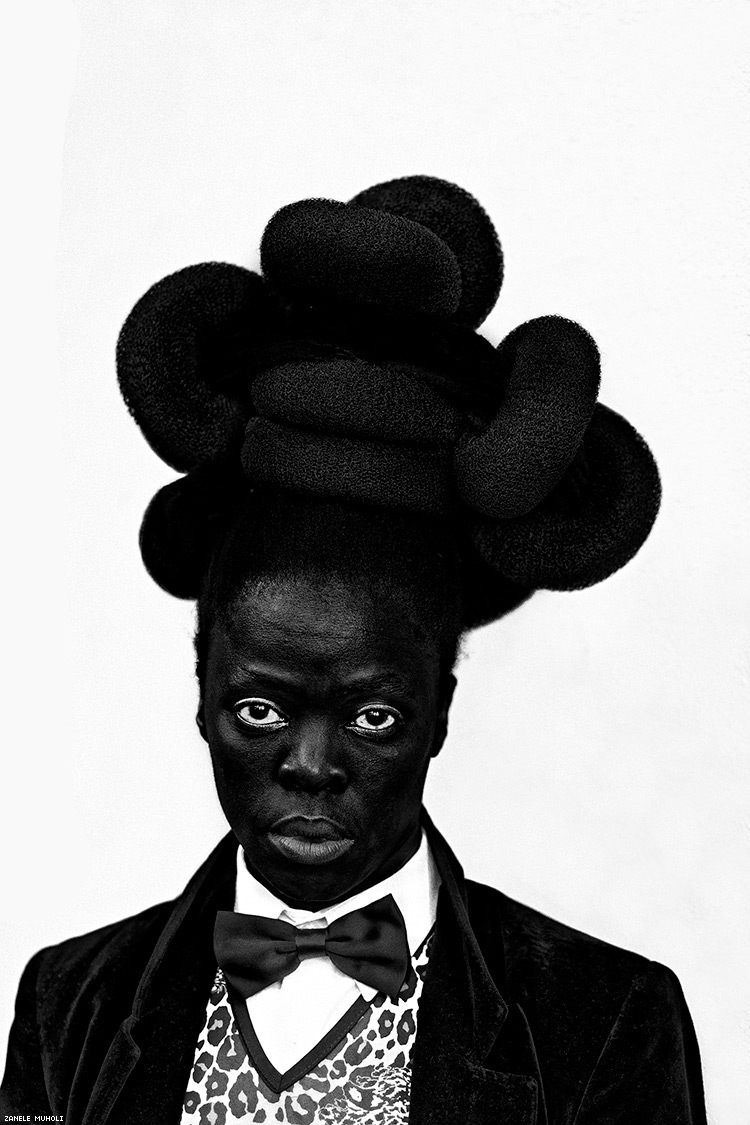

The work Somnyama Ngonyama, or Hail the Dark Lioness, exposes Muholi’s alter egos, the persons they imagined they would have become under different circumstances. It began as a quest to chronicle 365 days in the life of a Black person, but they were depicting more than just themselves. Portraits, named after their mother and other women they knew, began depicting them as defined by their environment, work, or recent events.

For instance, Bester I, Mayotte, 2015 features Muholi staring at the viewer dead-on, with darkened skin and numerous clothespins clipped to their hair, forming a headdress, and attached to their ears as jewelry. Bester V, Mayotte, 2015, another in the series, portrays them in the nude with another makeshift headdress, this time composed of metallic scouring pads. And in Thulani II, Parktown, 2015, Muholi commemorates the police murders of 34 miners in South Africa’s 2012 Marikana massacre, wearing nothing but a miner’s helmet and goggles. These pictures represent a literal elevation of Muholi’s humble beginnings — and the current events that were impacting their soul.

Before Muholi found their power in photography, they worked as a reporter for, in their words, a “media house” called Behind the Mask. They “discovered rich content in different townships” and soaked up a bevy of stories about the real South Africa, the one that wasn’t being portrayed in dominant media. After, it folded due to a lack of resources and Muholi was inspired “to work on content about us that isn’t dependent on [outside] resources.”

In 2006, Muholi developed Inkanyiso (meaning “illumination” in Zulu) as a digital platform for queer media and activism “in response to the lack of visual histories and skills training produced by and for LGBTI persons, especially artists (in the form of photography, film, visual arts, and multimedia).” Three years later, it grew into a full-fledged organization and now boasts seven volunteer contributors (according to their website) and a mobile school of photography, educating community members on how to also be agents of documenting the world around them.

Through the organization, Muholi has created opportunities for younger Black LGBTQ+ community members to hone in on their strengths. Throughout our conversation, Muholi makes mention of Lerato Dumse, their work partner who handles everything from coordinating the logistics of the visual activist’s special projects to writing accompanying reports on their findings in South Africa. “Lerato means love,” Muholi says with pride, later telling me they consider Dumse and their ensemble of artists and journalists (including Yaya Mavundla and Thembela “Terra” Dick) like a family.

Dumse was a journalism student at Tshwane University of Technology when she first met Muholi a year after Inkanyiso was officially registered an organization with South Africa’s Department of Social Services. The self-described introverted loner came to be forever documented in a Faces and Phases portrait titled: Lerato Dumse, KwaThema, Springs, Johannesburg, 2010. In it Dumse, clothed in a striped button-up, with a freshly shaven head of hair, carries a ruminative stare. This session served as the beginning of a powerful mentorship.

“I’d say I’ve learned a lot of life lessons from Muholi in how to deal with people, learning to love people, learning to open up space, learning to give, learning to be calm, learning when to talk, learning how to respond to things,” Dumse says. “I’ve learned to become a better human being and approach life more strategically.”

In recent years, Muholi’s work has reached far beyond South Africa. Renowned art curator and creator of the Black Contemporary Art blog Kimberly Drew (who also guest edited this magazine) introduced the Tumblr generation to the artist in the early 2010s. She was immediately taken by how Muholi so thoroughly integrated building and platforming progressive notions of identity in their artistic process.

“Muholi’s work is representative of a community. Their self-portraiture and Faces and Places shows the network they are bringing wherever they’re showing the work,” Drew says. “And [the subjects’] names are attached, which is very different from the history of photography where people’s identities are muted by virtue of documentation. There is a way that we look at Muholi’s work from the perspective of the people who are in it.”

Drew also lauds their technical skill, mentioning their “incredible control over light and color.” This speaks to the fact that Muholi has never relied simply on the content and context of their works to carry them. They are meticulous about every detail: the right amount of contrast between the whites of the eye and the melanin in their skin, dulling the shine of hyper-glistening surfaces, the grain in the texture of fabrics and materials. It’s these considerations that drew New York’s Yancey Richardson Gallery to represent them, and undoubtedly a part of why they’ve become so internationally acclaimed — their work has been exhibited in major American art institutions, like the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Museum of Modern Art.

Throughout the years, Muholi’s work both on the artistic and activistic fronts has gained critical recognition. In 2015, they were shortlisted for the Deustche Borse Photography Prize. A year later, they received the Infinity Award from the International Center of Photography Chevalier de Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. An Honorary Fellowship of the Royal Photographic Society came just last year. And in April, Amref Health Africa, the largest Africa-based healthcare nonprofit, honored Muholi with the Dr. Tom Rees Visionary Award for “creating exceptional work that educates, inspires, and emboldens the viewer through challenging times.”

When asked their thoughts about these moments of elevation, Muholi offers a nonplussed response. “They might be exciting, there might be entertainment attached to them, but in true honesty, all of these awards, trophies, and honors are political,” they say. “Honestly even my communicating or conversing with you is political, in which I have a choice to say I’m taking this job or I’m taking this honor or I don’t.”

What’s clear about Muholi is that they are not looking for validation outside of their community. Their work doesn’t simply exist for aesthetic and accolades; it serves a simple yet grand function to document the world around them with a sense of urgency to ensure that their people — particularly Black South African LGBTQ+ folk — will never be erased. The power for them is not wrapped up in how many galleries their works enter or how many times their name is shortlisted for an award. Throughout the interview, they point out that even this very cover story is long overdue “in a year when Americans are celebrating 50 years since the Stonewall Riots, and at home in South Africa, where our community is celebrating a quarter-century of democracy.”

“This interview is a statement or a testimony of survival. We’re really not talking art,” Muholi declares. “And I appreciate that I’m speaking to a person who probably feels like me, a person of color or a Black person — whether in America or in Africa — because you know for sure where you’re seated, that this is not a position of comfort. This seat is hot, therefore we cannot dare to be callous.”

Images (C) Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of the artist, Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York, and Stevenson Cape Town / Johannesburg.

Clarification: This piece previously featured an incorrect spelling of Zanele Muholi’s sister’s name, Ntombizane. Also, there was previously a line with phrasing on Muholi’s participation in the 1994 South African presidential election insinuating their voting preference. It has been updated accordingly.

Zanele Muholi one part of a double cover for Out‘s May issue. Guest edited by Kimberly Drew, the issue also features Ruth Bell by Marilyn Minter on the cover. To read more, grab your own copy of the issue on Kindle, Nook, Zinio or (newly) Apple News+ today. Preview more of the issue here and click here to subscribe.

Content retrieved from: https://www.out.com/art/2019/4/23/zanele-muholi-forever-changed-image-black-queer-south-africans.